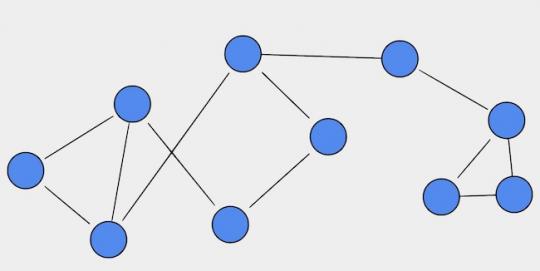

As the hours add up on this project, you start asking yourself why it feels worth it. The answer: connectivity; the appeal of linking things: devices to the Internet, blinking lights to the the cloud, one person to other people, people to a location.

That's what's exciting about the Internet, hypertext, smartphones, and the Internet of Things, over-hyped as that phrase is.

Connectivity is the satisfying payoff. Or at least it used to, before the social networks started turning sour.

Now Twitter is a cesspool: everybody is "clapping back." Facebook is a scam and a hustle. Now connectivity feels kind of used by surveillance capitalists, Russian hackers, and scheming, VC-funded startups.

But wait, at the hyperlocal level, doesn't it still work? In the real world, connectedness still has some of the power that fueled the growth of the Web, and Web 2.0.

Hypertext, which can be defined simply as text that contains links to other texts, also still works. In fact, hypertext was working before the Web, sort of. It's a concept that goes back to the mid-1960s.

It wasn't easy to warm up to, before hyperlinking hit the cultural jackpot in the mid-1990s, when the World Wide Web caught fire. Before the Web, hypertext sounded interesting theoretically. Reading an actual hypertext project was almost always more trouble than it was worth. You know, you tried.

Still, hypertext had its fans. In the 1970s, Roland Barthes was proposing a model in which text composed of blocks of words or images could be linked electronically by multiple paths in a open-ended perpetually unfinished textuality: "a galaxy of signifiers." Michel Foucault was on to the same idea with his "network of references."

Teilhard de Chardin, the French theologian and paleontologist, got positively theological about connectivity. In the 1940s and '50s he was writing about how mankind was evolving into a super network of human minds, knitted together into a global consciousness. Kind of like the Internet, when you think about it.

Teilhard de Chardin

de Chardin saw the earth as an evolving globe, increasingly clothing itself with a brain. In de Chardin's vision, everything is connected in a sacred web of divine life. As humans weave themselves together into neural nets, a global consciousness will emerge.

This is why de Chardin was embraced as a theologian for the Web by Internet/media thinkers like John Perry Barlow and Marshall McLuhan. And why if you want to push hyperlinking to the mystical max, de Chardin is probably your guy.